Ronnie Paul is a seasoned writer and analyst with a prolific portfolio specialising in climate change at Africa Digest News.

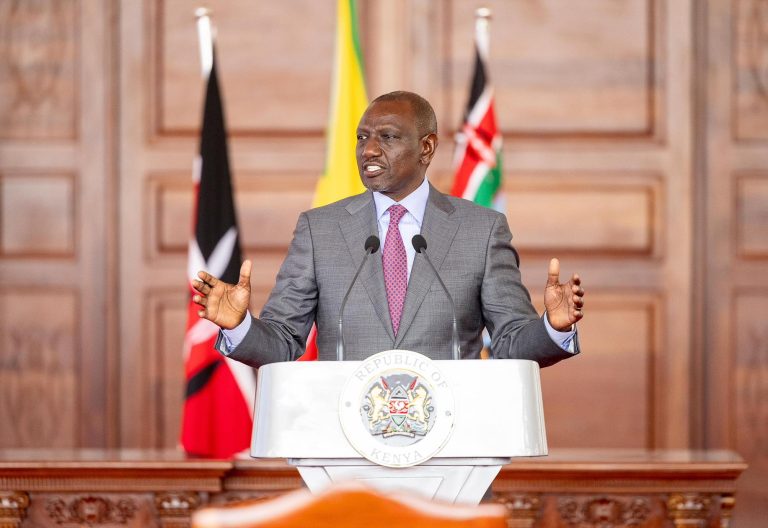

President William Ruto’s recent admission that Kenya is rationing electricity during peak evening hours has ignited a fierce national debate: Is Kenya facing a genuine power crisis, or is the government setting the stage for new tariffs and politically convenient narratives?

Speaking on November 5, Ruto acknowledged that Kenya is deliberately cutting power to some regions between 5 p.m. and 10 p.m. to keep the national grid from failing under surging demand. “Our energy haitoshi,” he said plainly.

His bluntness stunned many. For years, his administration has insisted that Kenya generates more than it consumes, with ambitions to export surplus power to neighbours.

Now, the government is conceding to daily load-shedding even as households face a recent Sh4-per-unit tariff hike. The disconnect is disturbing, and Kenyans want answers.

The Reality Check: What the Numbers Actually Show

On paper, Kenya’s energy story looks enviable.

- Installed capacity: ~3,840MW (EPRA, mid-2025)

- Peak demand: 2,362–2,412MW

- Main sources: Geothermal (~900MW), hydro, wind, solar

- Imports: Ethiopia (200 MW), Uganda (100 MW)

That should imply a comfortable surplus. But the grid’s reliability depends on when power is available not the headline number.

Here’s the catch:

- Solar collapses after sunset, right when demand spikes.

- Hydro output plunges during droughts, cutting generation by up to 30%.

- Geothermal plants run below capacity, with KenGen operating at just 70%.

- Transmission gaps and ageing infrastructure further squeeze evening supply.

So yes, supply exists, but not always at the right hour. Kenya’s “surplus” evaporates between 5 p.m. and 10 p.m., when homes, shops, and factories all lean on the grid at once.

And despite expanded rural electrification, national access has jumped from 37% in 2013 to 79% in 2025; reliability remains erratic. Counties like Kiambu and Kajiado still endure scheduled interruptions multiple times a week.

Is This Crisis Real or Manufactured?

The president’s statement has split analysts into two camps.

1. The Pro-Crisis View: Demand Is Outpacing Supply

Supporters of Ruto’s position say Kenya is experiencing:

- Record consumption fuelled by industrialisation, EV uptake, and urbanisation

- Weak hydro seasons triggered by climate change

- An over-reliance on imports that fluctuate with regional availability

- A grid not designed for Kenya’s new 24-hour economy

From this angle, load-shedding is a necessary stopgap to avoid a catastrophic nationwide blackout.

2. The Sceptical View: Mismanagement, Not Shortage

Critics argue that the crisis narrative is misleading.

- Installed capacity still exceeds demand by 1,400 MW.

- Kenya Power continues to underuse cheaper geothermal.

- No major plant has been commissioned in three years despite heavy borrowing.

- Excess capacity allows room for smoother evening balancing if managed well.

Some accuse the government of manufacturing scarcity to justify higher tariffs or new IPP contracts, pointing to opaque procurement deals and longstanding governance issues in the power sector.

The underlying frustration is clear: Kenyans are paying more than ever for electricity yet getting less of it.

READ ALSO:

Why Kenya Could Become Africa’s EV Market Leader by 2030

What Kenyans Are Saying: Outrage, Scepticism, and Concern

Social media erupted after Ruto’s remarks:

“What happened to exporting excess power?”

“Ruto is creating a crisis to borrow more money.”

Public trust, already strained by rising living costs, is wearing thin.

With investors jittery and manufacturing costs climbing, business leaders warn that power instability threatens Kenya’s competitiveness, particularly in the president’s cherished “24-hour economy” vision.

So Does Kenya Have a Power Crisis or Not?

Yes, but not the kind being implied.

Kenya does not have an outright generation shortage. It has a timing, planning, and reliability problem:

- Generation is mismatched with peak demand.

- The grid remains fragile despite upgrades.

- Renewable variability isn’t backed by sufficient storage.

- Key plants are underutilized.

- Policy signals have been inconsistent.

Load-shedding is happening, but it’s happening because the system is poorly optimised, not because Kenya lacks megawatts.

Ruto’s honesty is welcome. But without decisive reforms, including modern storage, grid upgrades, transparency on IPPs, and optimised geothermal dispatch, the crisis risks becoming self-inflicted.

Bottom Line

Kenya is not “running out” of electricity. It is running out of coherent planning.

If Kenya wants to industrialise, grow exports, and run a 24-hour economy, the solution isn’t just more generation but smarter management of the power it already has.

Kenyans deserve clarity, not slogans. The conversation now must shift from “haitoshi” to how do we fix it?