Ronnie Paul is a seasoned writer and analyst with a prolific portfolio of over 100 published articles, specialising in climate change at Africa Digest News.

At COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan’s delegate Ralph Regenvanu held up a simple pie chart: 20 rich countries caused 78% of historical emissions since 1850.

Then he asked for the bill. This moment reflected decades of frustration from the Global South, where nations like Vanuatu, responsible for less than 0.03% of cumulative CO₂, face existential threats from rising seas and supercharged storms largely fuelled by industrial emissions from the US, EU, and others.

As 2025 unfolds, with COP30 having happened in Brazil, the push for reparations has intensified, blending moral imperatives with legal muscle.

Yet, the fight reveals deep divides: Vulnerable countries demand trillions in grant-based support, while historical polluters offer loans and half-measures, perpetuating a cycle of debt and disaster.

The Math of “Carbon Debt”

“Carbon debt” quantifies the imbalance: historical emissions from wealthy nations have loaded the atmosphere with CO₂, forcing the Global South to foot the adaptation bill.

Carbon Brief’s 2025 analysis updates its landmark 2023 study, showing cumulative CO₂ from fossil fuels, cement, and land use from 1850 to 2024 totals ~2,600 GtCO₂ globally.

The top 20 emitters, led by the US (509 GtCO₂, ~20% share), the EU (collectively ~25%), and others like the UK and Germany, account for ~78%, per Our World in Data visualisations aligned with the pie chart Regenvanu displayed.

This debt compounds. A PNAS study introduces “net-zero carbon debt,” factoring historical emissions against a nation’s fair share of the 1.5°C carbon budget (~420 GtCO₂ remaining as of 2025).

Western Europe and North America could accrue debt by 2030 if emissions don’t plummet, owing trillions in equivalent value estimated at $1-2 trillion annually by 2035 for adaptation alone, per UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report.

For context, Africa’s share? Just ~3%. Yet, the continent faces $1.6 trillion in adaptation costs by 2035. These calculations, rooted in Global Carbon Project data, underscore reparations not as charity, but as settling an overdue account.

Barbados PM Mia Mottley’s Bridgetown Initiative and the Push for Debt-for-Climate Swaps

Enter Barbados PM Mia Mottley, whose Bridgetown Initiative launched in 2022 and updated to “Bridgetown 3.0” in 2024, reimagines global finance as a tool for equity.

At its core: debt-for-climate swaps, where high-interest debt is exchanged for commitments to resilience projects, freeing fiscal space without new loans.

Barbados pioneered this in 2024, swapping $165 million in bonds for investments in water security and ecosystems via partnerships with the Inter-American Development Bank and The Nature Conservancy.

The initiative demands tripling MDB lending to $100 billion more annually, rechanneling IMF Special Drawing Rights from rich to poor nations, and embedding “disaster clauses” in debt contracts to pause payments post-catastrophe.

By 2025, it’s gained traction: Ecuador’s $1.6 billion debt-for-nature swap protected the Galápagos, while Costa Rica issued blue bonds for coastal resilience.

Mottley, a 2025 Zayed Award honouree, frames it as “global fraternity”: swaps could unlock $500 billion globally by 2030, per Project Syndicate analysis, turning debt traps into adaptation engines.

Yet scaling requires creditor buy-in, which is elusive amid rising Global North debt.

New Voices: Brazil’s Amazon States Demanding Payment for Standing Forests, Africa’s Demand for $1.3 Trillion Annually by 2035

The chorus grows louder from the frontlines. In Brazil, Amazon states like Amazonas and Pará are demanding payments for ecosystem services, arguing standing forests absorbing ~2 GtCO₂ yearly are a global public good.

At COP30, Brazil launched the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), a $4 billion annual fund rewarding 74 tropical nations for zero-deforestation, with 20% direct to Indigenous communities.

Backed by the Forest & Climate Leaders’ Partnership, it could mobilise $15 billion yearly via carbon markets and bioeconomy investments, per Reuters. The Floresta+ Amazon project has already disbursed R$17 million (~$3 million) in 2025 for conserving 14,000 hectares, proving the model.

READ ALSO:

Understanding Climate Finance and How We Can Make It More Effective

Africa’s voice is bolder: the African Group of Negotiators (AGN) demands $1.3 trillion annually by 2035 in grants, not loans, for adaptation, rooted in the continent’s 3% emissions share versus 75% of future warming costs.

At AMCEN-20, AGN chair Dr Richard Muyungi called it “compensation for historical wrongs,” aligning with UNCTAD’s $1.46 trillion estimate by 2030.

The Baku-to-Belém Roadmap nods to this scale-up, but COP29’s $300 billion falls short, sparking outrage as “unacceptable.” These demands signal a shift from pleas to assertions of sovereignty over shared planetary resources.

Pushback from the US and EU and the Legal Cases That Might Force Their Hand

Resistance is fierce. At COP29, the US and EU coordinated a “gentle but firm” pushback, insisting obligations lie within UNFCCC frameworks, not expansive reparations.

The EU deemed draft texts “clearly unacceptable,” refusing specifics on contributions beyond the $100 billion goal (met late in 2022 at $116 billion).

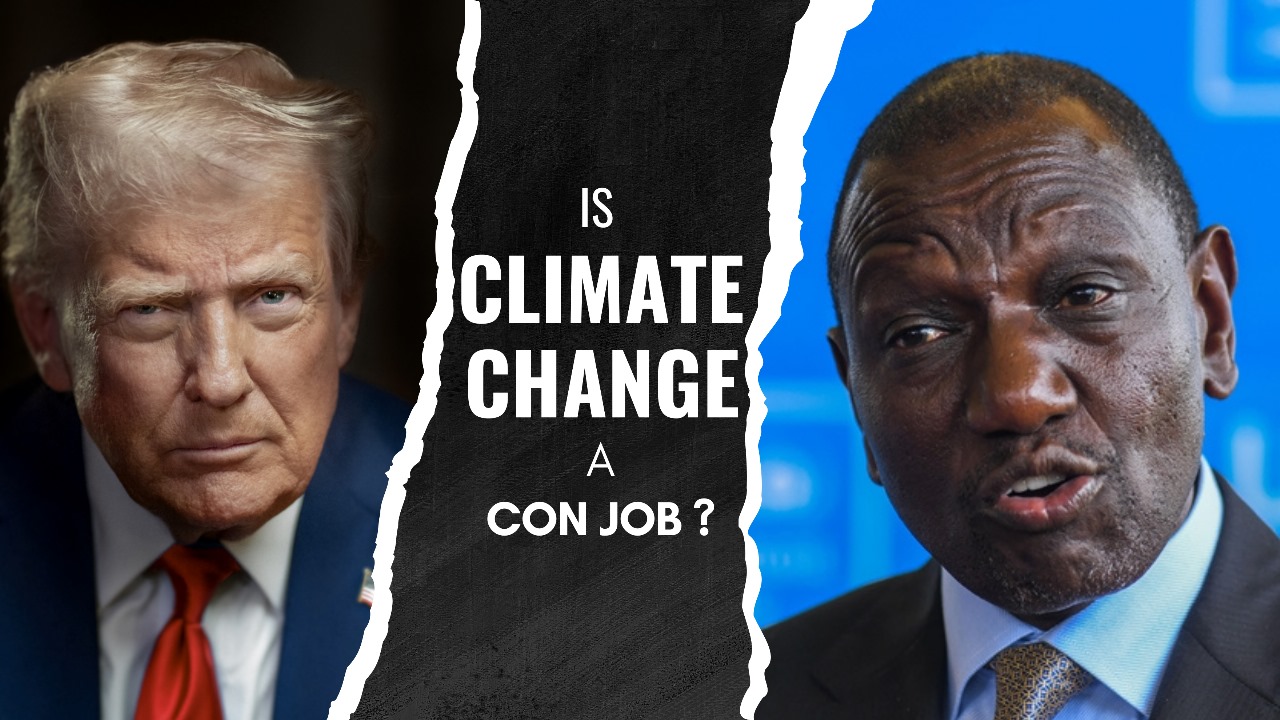

Domestically, EU ministers look at costs amid defence hikes, while Trump’s US rolls back regulations, calling climate a “con job.” This echoes historical stances: no “reparations” language, only “finance” as voluntary aid.

But courts are intervening. The ICJ’s July 2025 advisory opinion requested by Vanuatu declares climate inaction a “wrongful act,” obliging cessation, non-repetition, and “full reparations” (restitution, compensation, and satisfaction) if causation is proven.

Rejecting US/EU arguments limiting duties to the Paris Agreement, it opens doors for suits by injured states.

Echoing the ECtHR’s 2024 KlimaSeniorinnen ruling (Switzerland violated human rights via weak policies) and 2025 enforcement findings, it bolsters cases like Peru’s Luciano Lliuya v. RWE (seeking proportional liability for glacier melt).

In the US, Honolulu’s Supreme Court win against fossil fuel firms (cert denied Jan 2025) signals municipal accountability. Globally, 2025 saw surges: over 100 cases invoke the ICJ for reparations, per the Sabin Center.

Reparations aren’t charity; they’re the interest on a loan the planet never agreed to take. As 2025 closes with COP30 , the Global South’s unified front, strengthened by judicial wins, presses for enforcement. Will the US and EU pay up or face the courts? The bill is due.